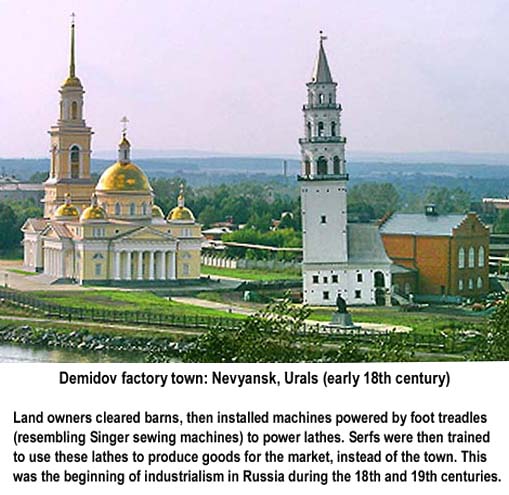

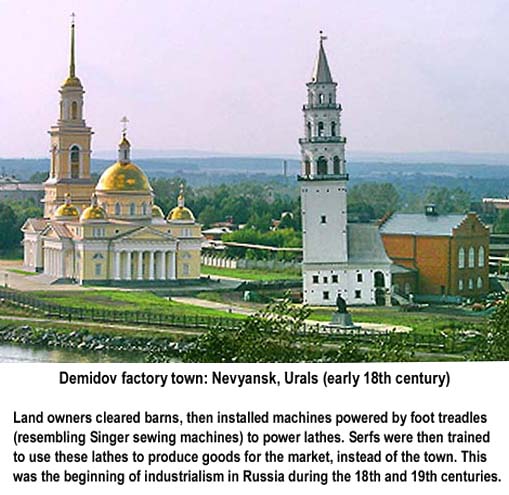

Peter the Great initiated a program of industrialization for Russia in the early 18th century. This page provides some background information on how the industrial factory system developed while serfdom was being eradicated.

"The history of Russian factory labor begins with the reign of Peter the Great. Factories of various sorts had appeared here and there in the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Russia - the first sign of industrial revival since the collapse of the Kievan artisan industry that followed the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century. ... [W]hen Peter the Great embarked upon his policy of forced industrialization...most of the industrial problems encountered by Peter turned out to be new problems for Russia. ...

"Chief among these problems, from our point of view, was to find a source of labor power for Russia's new factories. Enserfed peasants were the natural choice. ...

"Moreover, insofar as industrialization was a state policy, instituted primarily to serve immediate military needs, it was essential to state interests that the supplying of industrial labor be carried out as systematically as possible, under governmental supervision, and that it not be subject to the unpredictable vacillation of a freely functioning labor market. In one form or another, bondage appeared to be the safest mechanism for the accomplishment of this purpose. ...

"If the factory in question was the private property of a serf-owning noble, located on his estates, no particular problem of labor supply existed, for the principle of barshchina [corvée] was structurally as adaptable to factory work as it was to field work. During the reign of Peter, however, the manorial factory was still very atypical. The merchants, foreigners, and adventurers who were called upon by the state to assume the new enterpreneurial functions lacked the direct access of the nobleman to serf labor, and such labor had to be supplied from other sources. ...

"Under these circumstances, the institution of what later came to be known as 'possessional' workers or peasants was a logical solution. ... the compulsory assignment of large numbers of peasants to permanent factory work was the only available method whereby non-noble enterprises could be maintained. The possessional method was formally institutionalized by an Imperial ukase [decree]. This ukase permitted persons of non-noble origin, merchants in particular, to purchase whole villages of peasants for their factories. The peasants, however, were to become the inalienable property not of the factory owner, but of the factory itself as it passed from owner to owner. What this meant, in effect, was the creation of a new and special category of serfs - factory serfs - whose freedom of movement would, if anything, be less than that of their manorial counterparts ..." 1, 2

"St. Petersburg was the region of Russia where factories resembling the mechanized capitalist enterprises of the Western European industrial revolution appeared the earliest and gained the most rapid predominance. Steam engines manufactured in Western Europe, probably England, had been introduced in St. Petersburg textile industry on a small scale during the reign of Alexander I. between the 1830's and the beginning of the Crimean War, the mechanization of St. Petersburg cotton mills proceeded rather rapidly, a development that was stimulated by the decision of the British government in 1842 to lift its restrictions on the export of machinery. At a time when hand-weaving still dominated in the textile factories of Central Russia, mechanical looms were already beginning to play an important role in the capital. ...

"In addition to their mechanization, many of the newer factories differed from the traditional private factories ... in that they were neither possessional factories nor the private property of noble families, but rather were organized and founded as European-type joint-stock companies." 3

Industrial sectors in which such factories first were created included:

Other factories included soap factories, breweries, food factories, piano factories, officers' uniform factories, and horse-drawn carriage factories. There were also sugar refineries, tobacco factories, and tanneries that were mechanized using steam engines, as opposed to unmechanized manufacturing enterprises such as rope works, carpentry, sawmills, breweries, and distilleries.

The hope was that these factories, which used 'possessional' workers or peasants on the estates or manors, would stimulate a form of industrialization as dynamic as that found in western European countries. This proved not to be the case, however. "Nor had the merchantry or the nobility engaged in manufacturing on their estates proved to be the bearers of economic progress and industrial development, as had the middle class in the West."10

Why couldn't this medieval form of factory succeed as a basis of industrialization? There were two major problems with these factories:

After the Great Reforms led by N. Miliutin, Zablotskii-Desiatovskii, Perovskii, Kiselev, Zarudnyi, Elena Pavlovna and others, 10, 11 and the rapid creation of railroads, banks, and joint stock companies led by Graff (Count) Sergei Witte, 12 industrialization could make rapid progress. Alas, it was too late. Given the slow pace of change with the choice of reform or revolution, the people decided: revolution!

As Russia evolved from an agrarian society to an industrialized society, it began to develop labor codes and criminal law codes. In 1845 two new labor codes were created:

For the most part, both of these articles were ignored by the factories. The tsarist government was aware of this, and thus complicit. It should also be noted that since most of the peasant workers were illiterate and serfs were typically not allowed to go to court, it would have been difficult for the workers to comprehend legal issues.

"In the early 1840's, 1,007 living quarters, inhabited by various types of St. Petersburg workers, were visited by members of a government commission. Of these only 411 were considered to be in good condition by official standards, that is, not overcrowded, well heated and lighted, clean, and dry; 428 were considered barely adequate by these standards, and 238 were described as being in very bad condition. Overcrowdedness meant, in the area visited by one member of the commission, 3,776 workers inhabiting 199 residences, or an average of nineteen workers to each apartment. Even in quarters that were described as good, the workers slept either on boards or, if the workshop itself served as their living quarters, as was not uncommon, on their own workbenches.

"Shortly thereafter, in 1847, some five hundred workers' quarters were examined by a second commission. This time conditions were found to be so unsatisfactory that the commission felt compelled to recommend the establishment of a legal minimum standard for cubic feet of space per worker and the construction of special houses or dormitories in various parts of the city, where homeless workers would always be able to find a temporary shelter at nominal cost. In addition, it recommended measures to reduce fire hazards, elimiate filth, and, in general, establish minimally tolerable living conditions for the working class population. The unhealthful conditions that led to these recommendations were further compounded by the fact that St. Petersburg hospitals, already suffering from an extreme shortage of space, often refused to admit an ailing worker regardless of the seriousness of his illness. On occasion the dead bodies of workers who had been rejected by hospitals could be found on the city streets." 13

The Shtakel'berg Commission (1862) found that while industrialization required rapid expansion of the labor force, the tsekhi (artisan guilds) limited the growth of a labor force. The emancipation of the serfs was a necessity if industrial workers and consumers (a proletriat) were to be created. However, for industrialization to progress, serfdom (and its feudal nobility), as well as tsekhi (medieval artisan guilds), would have to be abolished. The Commission also recommended that once the serfs were emancipated, Articles 1791 and 1792 be stricken from the books, as these articles applied specifically to posessional and manorial factories during the time of serfdom. However, an examination of the Digest of Laws of 1873 shows that the laws of 1857-1864 remained in force; the Shtakel'berg Commission's recommendations were never implemented.

The factory workers (proletariat) were totally impoverished, usually illiterate; some so sick and cold and starving that they had no recourse but drunkenness [as evinced by the number of kabakov (taverns) in each chast' (<<часть>>) or district, or each kvartal (<<квартал>>) or quarter or ward.] The greatest proportion of deaths due to Cholera, Typhus, and Scarlatina afflicted these workers, causing a disproportionately high death rate. Most of these factory workers were aged 16 to 25 (young: they should be very strong). The authorities were not interested in examining why factory workers were dying in such great number; they employed a theory that ascribed deaths and illness to climate. (Climate is something that cannot be ameliorated.) The police understood that this was a new phenomenon caused by overcrowding, filth, etc., but they were not equipped to understand it as a symptom of a social problem. Instead, they blamed the situation on the bad climate, and the bad morals of the working classes.

Finally, a small group of physicians examined what was happening. The physicians feared that they would be attacked by the government for identifying the true cause of the soaring death rate for factory workers as being socially determined: poverty and filth in factories and in the homes that the factory workers lived in. First Dr. Giubner, then Dr. Arkhangel'skii, identified this problem as a social problem that the tsarist government officials were not addressing. Fearing the tsarist officials, a physician of the Arkhiv sudebnoi meditsiny i obshchestvennoi gigieny (Archive of Legal Medicine and Social Hygiene) identified only as Dr. "R", publicly identified the social causes of the high death rates. Dr. "R" noted that the climate in St. Petersburg was effectively the same from year to year, yet the death rates were steadily increasing: obviously, the climate was not the cause.

Dr. "R" felt that if the lethal working conditions were ameliorated in England, these same working conditions must be rectified in Russia by introducing factory legislation that covered health, sanitation, safety, education, housing, the length of the work day, child labor (10-year-olds working at night) and labor by pregnant women (children and women were paid lower wages). Such legislation required enforcement by expert factory inspectors. While the tsar and his police felt moral behavior, debauchery, and depravity could be controlled by repression, and superficial religious indoctrination, the Arkhiv doctors considered such behaviors to be the result of the social conditions: the cellar apartments were the cause of vice just as they were the cause of disease. 14

When one considers that factory owners were drawn from the pomeshchiki (landed nobility) and that tsarist chinovniki (officials) were also usually recruited from pomeshchiki, it is not surprising that the tsarist government and industrial leaders opposed such reforms.

This section briefly describes three of the hundreds of strikes that occurred in Russia from the latter half of the 19th century, till the 1917 revolution.

In 1870, the lack of an enforced set of labor laws or labor codes resulted in a dispute that ultimately became St. Petersburg's first sustained strike. Grievances arose at the Nevskii Cotton-spinning Factory between skilled factory spinners and unskilled workers (fabrchniya ludi) based on inequalities of wages for piecework and holiday pay. Factory management intervened on the side of the unskilled workers, deducting money from the monthly wages of the skilled spinners. The skilled workers tried repeatedly to get an agreement with management to reimburse the wages that had been deducted, and belatedly added a demand for more wages (which they later retracted). Management retaliated by inviting the skilled spinners to leave the factory.

The spinners appealed to local government authorities for assistance, and got the impression that the matter would be investigated. After approaching factory management a second time, and being rebuffed, the spinners engineered a work stoppage at the factory by preventing all employees from entering the building. Management retaliated by removing the spinners' internal passports from the factory office. When confronted by two angry spinners, the Factory Superintendant said the spinners should put their demands in writing. Although the Deputy Chief of Police pleaded with the alleged strikers to return to work, saying that their actions violated factory rules, the workers felt their grievances were legitimate and chose to pursue their case in court. Sixty-two spinners were indicted for striking, and the tsar informed.

The laws and customs for managing labor issues in Russia all dated from 1866, shortly after the emancipation of the serfs. (Serfs have no right to due process in a court of law.) "[F]or the most part, those laws and customs that did exist were confused, widely ignored, contradictory, and given the needs of modern industry, out of date." 16 (Articles 1791 and 1792, mentioned above, ceased to apply after serfdom ended, although they remained on the books.) The main charge against the defendants was that they had violated article 1358 of the Criminal Code of 1866: stopping work prior to the expiration of their contract, for the purpose of compelling management to raise their wages. However, though the prosection was required to prove (1) that the defendants conspired in advance to plan their action; (2) that the goal of the conspiracy was to obtain a wage raise; (3) that they intended to stop work prior to the end of their contract to achieve their goal; and (4) that a clearly-understood contract, requiring the defendants to work until a specified date beyond the date of the alleged walkout, actually existed; it was never able to do so.

During the trial it was shown that most employees at the factory had been hired with a verbal contract, not a written contract, and were never given workers' booklets, both of which were required by law. The only document where conditions of employment were set forth was the list of internal factory regulations, posted on the walls of each shop. Moreover, by ordering the strikers off the premises, factory management were violating their own regulations.

In view of the fact that factory management was breaking labor law and could not prove that the strike had been planned by company personnel, the sentences mandated by the court for the alleged strikers, were exceedingly light. The tsar refused to accept these court sentences. Determined to avoid the strikes that were beginning to plague the rest of Europe, and convinced that such strikes had to be instigated by outside agitators and socialists, the tsar arbitrarily overturned the sentences of six of the striking spinners, and sent them into exile.

"[T]he decision to revert to administrative methods was a severe blow to the integrity of judicial reform. It removed an entire area of litigation from the courts, plus guaranteeing that the complicated problems of labor-management relations could not be worked out to a gradual process of judicial ruling. ... The [M]inistry [of Internal Affairs] instructed the St. Petersburg censorship committee to curtail the publication of such articles [discussing strikes such as the Nevskii Cotton-spinning Factory strike]. The article censored ... had gone on to predict that if such rulings continued to be made by the courts, they would only serve to intensify the already-existing oppression of workers by manufacturers." 17

The tsar had concluded that outside socialistic agitators were the cause of the problem, and that these could be dealt with in an arbitrary manner, like censorship, ignoring the judiciary, and exile. Others suspected that these problems would only intensify, and not disappear.

The Kreenholm Strike of 1872 (<<Кренгольмская Стачка>>), was a major strike, much larger than the Nevskii Cotton-spinning Factory strike.

Kreenholm was an island settlement on the Narova (or Narva) River, in Estland (now Estonia), near the border of Petersburg province. The factory was comprised of four buildings, or "corpusses": two spinning factories totalling 360,650 square feet, and two weaving factories totally 206,855 square feet. It held over 64,000 spindles, and nearly 1,000 looms. At the time of the first strike, between 6,000 and 7,000 men, women and children worked there.

"... Part company town and part preindustrial fiefdom or barony, Kreenholm managed to escape the usually watchful eyes of Russia's central police appartus until its managers lost effective control over law and order. [It] was governed in its early years more like a moat-encircled medieval castle than the modern industrial complex it otherwise resembled." 18

As the factory was geographically isolated (distant from Narva, Reval, and St. Petersburg, and isolated from raznochintsy intelligentsia), there was no question of any "outside" socialist agitators. Moreover, although mistreatment of workers at Kreeenholm was widespread, the men, women and children19 who labored there were segregated by their roles (weavers and spinners worked in separate buildings); thus, they had no perspective on how widespread was the mistreatment of Kreenholm employees. However, when a cholera epidemic began to throw workers at Kreenholm into a panic, a chain of events was set off that ended the isolation of workers from each other. This same chain of events also irrevocably broke Kreenholm's isolation from the Russian government.

The first workers at Kreenholm to suffer from the cholera epidemic were construction workers. In a panic, on August 9, 1872, the stone masons asked for back pay and permission to temporarily return to their villages until the cholera subsided. When management refused this request, the masons (chernorabochie who were merely looking for protection from someone with higher authority) sought help from the Russian government.20 This was the first public airing of any complaints by Kreenholm workers beyond the boundaries of the factory, and while it was ultimately unsuccessful it prompted the Gendarmes in Narva to ascertain that Kreenholm had taken proper precautions against the cholera. The masons were threatened with dismissal if they left their jobs (presumably justified because in leaving they would be breaking their contract), but a large number of them opted to leave anyway. However, when the worst of the cholera had passed and the masons began to trickle back, they were rehired without penalty. 21

On Monday, August 14th, just as the cholera was just about to peak, about 500 of the factory's 900 weavers left their looms, gathered in front of the factory director's office, and announced their refusal to return to work under existing conditions. Though it is felt that their mood had been fanned by the panic over cholera:

"'[T]he actual stimulus for a strike ... came from a minor fact. It happened that the director, probably for hygienic reasons, ordered that all windows at the factory remain open and decleared that anyone who closed a window would be subject to a 5 ruble fine. It became so cold in the factory that it was completely impossible to work."22

More than the cold (or the harmful effects of humidity on their yarn), the weavers — who were already beset by fines to pay for repairs whenever their aging, ill-maintained equipment broke — were probably driven to act by the "humiliating threat of yet another fine ... unleashed in the midst of an enervating, life-threatening contagion." 22

The director ultimately agreed to order the windows closed, but this early victory, plus the presence of police and other state officials on the factory grounds, emboldened the weavers. They presented a list of general demands to management, most of which amounted to a return to past conditions at the factory, but some of which asked for clear guidelines about fines and penalties charged to weavers. Management asked the weavers to wait a week, until the factory owners arrived, to present their grievances.

When "local police and medical personnel busily cleared residents from their rooms, emptied outhouses, and applied disinfectants ... unusual opportunities were created for social interaction among workers whose work patterns and living arrangements were normally segregated ..." 23 The sharing of stories of abuse permanently changed the dynamic between the workers and management. By the time the owners arrived on August 21st, they were met by a crowd comprised of both weavers and spinners. This was significant because spinners (who could produce highly marketable yarn for sale whether the weavers were working or not) were capable of creating a bottleneck in the production process or even stopping production entirely. 24

The events of August and September 1872 never really resulted in a "strike". There was some besporiadki in early September 1872 that resulted in the arrest of seven "instigators" (zachinshchiki, or <<Зачинщики>>) 25, but none of the weavers' or spinners' demands included an increase in pay. However, management refused any worker demands that amounted to giving workers a voice in the running of the factory. It dragged its feet to post a schedule of tarrifs (fines and fees for damaged equipment, which were to be set in consultation with worker representatives), and when the tarrifs were finally posted, they amounted to fines that exacted the full cost of new replacement parts from the workers, ignoring depreciaton. This was a ludicrous demand from people who were profiting highly from the workers' labor.

An uneasy peace reigned at Kreenholm, where the workers were now sensitized to each others' grievances. The workers at Kreenholm were not yet politically aware, but that was about to change.

The seven zachinshchiki who were arrested during the unrest at Kreenholm were briefly incarcerated, and then barred from returning to Kreenholm for one year after they had served their sentence. This insured that the men would go elsewhere to seek work. At least two of them were thus exposed to labor disputes in other locales, and to raznochintsy intelligentsia, and became radicalized:

"After leaving prison in November 1872, Preisman remained in Reval while Shakhovskoi lobbied for his passport and pay. Then, just about the time he turned twenty-one, [he] boarded the train for St. Petersburg, the nearest location of textile factories outside his restricted zone. There he worked in at least three different factories over the next fifteen months. [One of the factories was a sugar factory.] [By the time] his year of banishment expired at the end of 1873 ... he was deeply involved in illegal 'study circles' (kruzhki) for workers, mainly his fellow weavers, organized by members of the group of radical intelligentsia known as chaikovtsy. His exciting new life included political debate in local taverns and secret meetings in the homes of students, one of whom remembered him as a militant promoter of strikes and firearms." 26, 27

"... 1873-74 marked the apogee of efforts by radical 'students' known as the chaikovtsy and some related groups to spread their political ideas among Petersburg workers. ... [B]ecause Gerasimov's interest in such circles coincided with a crackdown by the Petersburg police, he was unable to establish a regular relationship with radical students until the winter of 1874-75, when he entered the circle of Viacheslav D'iakov. It was in this congenial milieu that he pronounced himself a revolutionary socialist. Withdrawing from factory work, he in effect became a full-time (but short-time) professional revolutionary." 28

In late 1874, illegal literature distributed to weavers in St. Petersburg, wound up in the hands of Kreenholm workers. 29 Moreover, in 1879, striking textile workers in St. Petersburg ("this time encouraged by real outside agitators") made plans to send a delegation to Kreenholm in quest of support, possibly a solidarity strike.30

"[I]f nothing else the incident suggests an awareness among Petersburg workers that at a time of crises there were thousands of potential allies less than a hundred miles to the west; despite the calm that seemed to reign there in the late 1870s, the Kreenholm factory's reputation as a potential locus of unrest apparently remained alive in the capital." 31

In 1882, unrest was rekindled at Kreenholm, prompted once again by fines and oppression. However, this time it was not the weavers who instigated the protests and demonstrations, but the spinners. (Weavers joined the protests, but not until the fourth day of the disturbances.) Also, the central demand from the spinners was a call for a higher piece wage. 32

"Despite the absence of serious violence, there was soon a request to the district military commander to dispatch a full regiment (here the memory of 1872 seems indisputable). Before the day was over three battalions of infantry were [sic] on route, a decision the tsar at once approved and lamented." 33

The strike showed that a now politically-aware proletariat would fight (even against the state military) for its rights. These kinds of strikes continued into the 20th century, and politicized the entire country.

The "Dickensian" working conditions, 34 living environment, and labor issues described above were recapitulated throughout Europe, and were the same as what Friedrich Engels, Jack London and Charles Dickens found in London, Manchester, and other English parrishes. However, Dickens ("The Conscience of the Nation") was uninterested in Russia, Belgium, Germany, or France.

|

adresnaia kontora or

<<Адресная контора>>

or expeditsiia or <<Экспедиция>> |

Otkhodniki had to report to a section of the police in urban locations

named the office of "adresnaia kontora" or "expeditsiia" (department). The purpose of

this office was to assign known addresses with a "billet" that specified

an explicit time period that the serf was permitted to live and work in

the urban center. The otkhodnik would then turn over his/her internal

passport (residence permit or <<вид на

жительство>>).

Thus the otkhodnik could no longer leave the town or city. Effectively,

the office of the "adresnaia kontora" became the new pomeshchik.

The pomeshchiki established such offices so that they could collect a portion of the workers' pay. Note that if factories seized the otkhodniki residence permits, then the otkhodniki would effectively not have a right to live in the city. This happened in England during the Great Coal Mining strike of 1842, where the coal miners (forced by the coal mines to live in company housing) were locked out of their company houses. |

| artel' or <<артель>> | Lower than a "tsekh" or guild, the artel' was an association of serfs that originated from a derevnia (small town) or celo (small town with a church). The artel' workers were usually employed on a pomeshchik's estate and engaged in similar, unskilled or semi-skilled work such as carpentry. Such workers were permitted to travel from their estate to urban centers and engage in labor. |

| banshchik or <<банщик>> | A worker that takes care of the bath. |

| barin or <<барин>> | A weathy, powerful person (or used sarcastically, to designate a person that falsely claims a high position). |

| besporiadki or <<беспорядки>> | Labor disorders. |

| chaikovtsy or <<Чайковцы>> |

The chaikovtsy were a group of narodniki (<<народники>>)

or populists, who were distinguished primarily by two views:

anarchism, and the idea of "going to the people". The St. Petersburg

branch of the chaikovtsy included Prince Pyotr Kropotkin. Other

narodniki active at this time included Vera Figner

36. Many of these

populists were motivated primarily by moral concerns (injustices

found in feudal Russia). Consider: justice was usually administrative

(arbitrary, inquisitorial, and imposed by an individual or a department

of the government), rather than being based upon law

codes administered by an impartial judiciary.

Some of the Kreenholm workers were imprisoned due to their interest in chaikovtsy kruzhki (study circles). This time period (1873 and after) may be considered the cradle of radical political expression in Russia: just on time to help activate and give direction to the newly created proletarians. Tsarist policies couldn't have created a more volatile political environment, guaranteed to support growing political instability. |

| chast' or <<часть>> | A city police district. Such districts were not "administrative" or "political" jurisdictions, these were only supervised and held under surveillance by the local police. |

| chorniy ponedel'nik or <<Чëрный понедельник>> | Black Monday. |

| chernorabochie or <<Чëрнорабочий>> | An unskilled, illiterate laborer. Areas of work included construction, transportation (coach drivers), handicrafts/temporary tsekh workers, servants, janitors. |

| chinovnik or <<чиновник>> | A chinovnik refers to a bureaucrat with a specific rank. Click here for additional information. |

| contract or <<Контракт>> | Free (serf) labor was based upon oral contracts between a pomeshchik and his serfs. Oral contracts were commonly employed as serfs were usually illiterate. These contracts began to be written in 1767 and were registered with the police. If any contracted serf that worked in an urban center left the area (which could mean left a factory "dormitory"), then this worker was treated as if he/she had commited the crime of illegally fleeing a manorial estate. |

| dvor or <<двор>> | Yard (of a house or building). |

| dvornik or <<дворник>> | A yard cleaner or sweeper of a house or building. |

| dvoryanin or <<дворянин>> | A governmental (Tsar's) steward (highest level in Russian society, an aristocrat). |

| fabrchniya ludi or <<фабричные люди>> | Typical name used for cotton-spinning, weavers or textile workers in general. In the textile industry, the work of spinners was considered to require less training and experience than that of weavers. Thus the weavers were considered to be a "labor aristocracy" or "rabochaia aristokratiia" (<<рабочая аристократия>>). |

| fabrika or <<фабрика>> |

Common name used for a factory, usually light industries for domestic products

including textiles (see also "zavod"). As factories were a new phenomenon,

their workers formed an entirely new social class as well, the class of

landless workers or the "proletariat". At first, the proletariat were viewed

as simply criminals or morally degenerate (caused in part by the lack of

adequate housing, starvation, lack of health and sanitation, etc.), but as

the proletariat grew from a miniscule number of people to a very large

number of people, it became clear that simply vilifying a class would not

serve as a useful description, nor provide a means of social control. Factories

were a new phenomenon, thus were not accurately described. Factories with less

than 16 workers were categorized as "workshops", and the name "fabrika" or

"zavod" applied only when there were at least 16 workers.

Click here to see an early Russian factory. |

| fenya or <<Феня>> | Fenya is the nineteenth century slang of the Russian underworld, sometimes referred to as "blatnoy yashik" (<<блатной язык>>) or the language of criminals and thieves. For examples of such slang in context, see in Vladimir Dal', "The Petersburg Yardkeeper", in Nikolai Nekrasov (Ed.), "Petersburg: The Physiology of a City", republished by Northwestern University Press in 2009. |

| guvernantka or <<гувернантка>> | A governess. |

| guvernyor or <<гувернёр>> | A teacher (male). |

| hozyain or <<хозяин>> | An owner of property (not necessarily land), often used to designate a "boss", often an owner. As owners were often absentee owners, thus the owner's on the spot representative (not an owner) would also be viewed as a "boss". |

| kabak or <<Кабак>> | A neighborhood tavern for the impoverished working class. |

| kabal'ny or <<кабальный>> | In 1816, the purchase of serfs from pomeshchik manors to be employed in posessional factories was abolished. Nevertheless, serf laborers were still needed. The 1816 law was evaded by contractual arrangements directly between the factory and the pomeshchik (the serf was not consulted). Such serfs were termed "kabal'nye" laborers or bonded or enslaved laborers. The notion that the problems encountered by the existence of a proletariate in western Europe would not take place in Russia because when the lack of work took place, the serfs could simply return to their originating manors was naïve: obviously this idealistic view of Russian labour was falling apart. With the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, the problem of the existence of a proletariate with state obligations would disintegrate. Problems with urban centers of industrialization: water supply, the supply of food, housing, sanitation and health, education, the exploitation of the labor of children and women, law and legality, and strikes had arrived in Russia. |

| kazarmy or <<Казармы>> | Barracks for workers (in urban or rural settings). |

| konyuch or <<конюх>> | An attendant for a horse. |

| krestyani or <<крестьяне>> | Peasants. |

| kruzhki or <<Кружки>> | Kruzhki were illegal radical worker "study circles", organized by the radical intelligentsia known as the "chaikovtsy". |

| kucher or <<кучер>> | A horse-drawn coach driver that sits on the coach bench, in the city. See also yamshchik. |

| kupechestvo or <<купечество>> | "First" guilds (merchants) were replaced by kupechestvo by the law of Catherine II (1785). |

| kvartal or <<квартал>> | A police quarter or a police ward in a large city. Such quarters or wards were not "administrative" or "political" jurisdictions, these were only supervised and held under surveillance by the local police. Another closely related idea is that of the "okolodki" (<<Околодки>>) or precincts. |

| lakey or <<лакей>> | A butler (clothes, boots, etc.). |

| les or <<лес>> | A forest. |

| lesnik or <<лесник>> | A forest keeper. |

| nyanya or <<няня>> | A nanny (babysitter). |

| otkhodnik or <<отходник>> |

Serfs who pomeschiki allowed to leave their estates, to work in a town or city

because it was to the pomeshchik's advantage. (Either the serf's labor was

temporarily not needed, or the pomeshchik could profit by taking a percentage of

the serf's earnings as obrok ["quit rent"].)

As posessional factories evolved, there was an increasing need for extra workers. "Torguiushchie" peasants had tacit permission from the government to work in the cities temporarily, while the government looked the other way. Slowly, such serfs began to displace possessional workers in factories, and began to be known as otkhodniki. Otkhodniki who were not attached to a tsekh were required to be attached to an address office ("adresnaia kontora" or "expeditsiia"). This allowed them to work in the city for limited periods of time (the time delimited by their residence permits, or internal passports), then return to the pomeshchik's manor at the time of planting and at the time of harvesting. Because they were compelled to travel periodically between the rural manors and the urban centers where factories were located, otkhodniki were considered an unstable workforce. Insofar as the otkhodniki were never permitted to be full-time factory workers, they were also seen as being unqualified to compete with European factory workers. This put factory owners in a permanent bind, since there was a constant shortage of trained workers. As Russia evolved from a feudal, agrarian society to a society with industrial factories, the otkhodniki were simultaneously both feudal peasants, and industrial factory workers. |

| poden'shchik or <<Подëнщик>> | A day laborer (unskilled, usually a chernorabochie). |

| pomestye or <<поместье>> | Estate (owned by a pomeshchik). Usually awarded as a gift for services. See usad'ba. |

| pomeshchik or <<помещик>> | Landowners, usually noblemen, but not necessarily (sometimes a dvoryanin or a merchant). |

| ponedel'nichan'e or <<Понедельничанье>> | People who can't afford to eat on Monday (after being paid on Saturday, going to church on Sunday, then getting drunk). By Black Monday, no more money for food. |

| povar or <<повар>> | A cook. |

| prachka or <<прачка>> | A woman that washes floors, clothes, etc. |

| proletariat or <<Пролетариат>> |

The proletariat is comprised of free laborers (not serfs, bound

workers, peons, slaves, etc.) who are landless. Basically posessing

no property, their primary value is their labor. While it is the

current view that the term "proletariat" is used only by Socialists,

bundists (unionists), and Communists, this is historically in error.

Circa 1820-1860, concerns as to what constituted the newly-emerging

proletariat class, and what the relevant social issues were, were

under very serious examination in ALL the states of Europe, precisely

because of the strikes, mutinies, revolts, etc. that

were taking places (for example, the "Canuts" in Lyon, France,

Robert J. Bezucha, "The Lyon Uprising of 1834: Social and Political Conflict in the Early July Monarchy", Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1974 (this is about the Canuts). |

| raznochintsy or <<разночинцы>> | People of miscellaneous ranks: lower nobles; non-hereditary nobles; discharged military men; even merchants, industrialists and peasants. Effectively, "nobodies", or people who were poorly educated or uneducated, sometimes identified with raznochintsy students (non-noble students) or the intelligentsia. Members of the intelligentsia, including raznochintsy students, attempted to create schools for industrial workers. As Sunday was the only day that workers might be able to attend such schools, these schools were called "Sunday schools" (<<Воскресные школы>>). The more conservative members of the tsarist government feared that workers might learn to combine and demand better pay and greater rights if workers attended these schools. The subject matter permitted was limited to reading, writing, arithmetic and religious subjects (morality: factory workers were viewed as being morally depraved). Subjects not permitted included history, foreign languages (workers could learn about "radical" movements in other countries), geography, science, and even the forbidden subjects such as ethnography (it might be more difficult to set Russians against Ukrainians, Ukrainians against Poles or Jews), and political economy (exploited workers might understand how they were being exploited). The highly motivated teachers drawn from the intelligentsia and the raznochintsy students, were quickly replaced by the tsarist government by noblemen, then orthodox priests. However, the tsarist authorities still feared these Sunday schools. Suddenly devastating "fires" appeared in St. Petersburg. It was claimed that these "revolutionary" activities were led by Sunday school attendees. The tsarist government never could find any revolutionary printed ideas or revolutionaries, but the Sunday schools were closed in 1862, in any case. |

| sad or <<сад>> | A garden. |

| sadovnik or <<садовник>> | A gardener. |

|

skotnik or

<<скотник>>

(skotnitza) or <<скотница>> |

A man (or woman) that tends larger farm animals such as cows, pigs, sheep, goats, etc. |

| stachka or <<стачка>> | A kind of conspiracy or agreement; a strike (most common usage). "Stachka" can be used to mean a strike by factory laborers, or an agreement between factory owners ("stachka kapitala", which included price fixing; fixed, inter-factory pay rates for factory workers; etc.) See also "zabastovka" or <<забастовка>>. |

| tsekh or <<цех>> |

|

| uborshchiza or <<уборщица>> | A cleaning woman (floors, furniture, statues, etc.) |

| ugol or <<Угол>> | A part of a room, such as a corner, paid for by poor people as a place to sleep. |

| Ura! U! U! or <<Ура–а–а!>> | Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah! |

| usad'ba or <<усадьба>> | An estate. Usually purchased. |

| vozmushcheniia or <<возмущения>> | Mutinies. |

| yamshchik or <<ямщик>> | Horse-drawn carriage driver (outside a city or between cities), see also kucher. |

| zabastovka or <<забастовка>> | Strike. See also "stachka" or <<стачка>>. |

| zachinshchiki or <<Зачинщики>> | Ringleaders or instigators. |

| zakonnost' or <<законность>> | Law and questions about legality, as applied to factory workers. |

| zavod or <<завод>> |

Common name used for a factory using heavy, metalic industrial machinery

(see also "fabrika"). As factories were a new phenomenon, their workers

formed an entirely new social class as well, the class of landless workers

or the "proletariat". At first, the proletariat were viewed as being simply

criminals or morally degenerate (caused in part by the lack of adequate

housing, starvation, lack of health and sanitation, etc.). However, as the

proletariate grew from a miniscule to a very large number of people, it

became clear that vilifying a class would not serve as a useful description,

nor provide a means of social control. Factories ("fabrika" or "zavod") were

defined as such when they had 16 or more workers. If there were 15 workers or

fewer, they were called "workshops".

Click here to see an early Russian factory. |

| Civil Hierarchy |

|

| Military Hierarchy |

|

© Copyright 2006 - 2019

The Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg Trust

Website Terms of Use

Website Terms of Use