Cloth was originally made by hand, using the spinning wheel.

However, by attaching many spinning wheels to a common axle,

the output of yarn could be increased several times over.

Using a water wheel (or even a wind-mill, if the wind is

sufficiently constant), the axle of the water wheel could

drive the multiple spinning wheels. A water wheel axle could

also be set to turn another axle connected by gears but at a

right angle to the main axel of the water wheel. Using a

steam engine fueled by coal, was a more powerful source of

energy that could be used to produce yarn. The energy derived

from a steam engine was not subject to weather, drought, etc.

Using fibers from the cotton plant, wool, flax, silk, etc.,

different kinds of cloth could be manufactured. Once the fibers

had been produced, power machinery was then used to weave

cloth, as well as lace.

As new machinery was invented for the cloth industry, the

process of producing cloth increased in efficiency, therefore

fewer workers were required. However, while such low-cost

workers provide a labour supply, these workers cost money.

Housing was required. Health costs rose, as producing coal in

mines as well as working with machinery in the cloth industry

was dangerous. The initial cloth manufacturing machines had

unprotected "belts" (cheaper not to cover the belts) and the

fingers, hands, arms, feet and legs of workers (and sometimes

the entire body) were caught in these machines, thus maiming

or killing the workers. Cloth fibers caused lung diseases,

just as coal-dust also caused debilitating lung diseases.

Industrialists wanted to drive down costs, but workers could

not live on slave wages (and they often starved to death, in

spite of the penal

workhouses and

those "transported" for

stealing food). Social instability could be predicted, and

social instability is exactly what happened. Governments do

not handle instability well, a problem that governing bodies

did not know how to solve (except by using violent repression

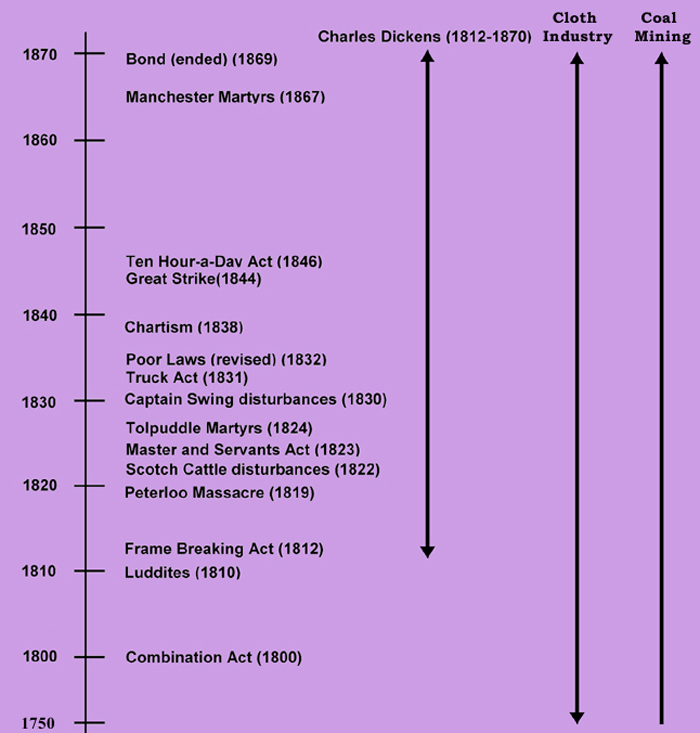

to maintain the hierarchical "class" structure). As a rough

indication of these times, consider the following incomplete

"time line". What is shown is how instable the government

was: it was not able to deal with the forces it had unleashed

in this new society based upon a Capitalist Industrial

Revolution. The Industrial Revolution had been born!

Also note how so many of these important

events took place during the life time of Charles Dickens!

The Chartists and Socialists established their own reading

rooms, which they filled with politically-oriented journals

and included writers such as Helvétius, Holbach,

Diderot, Shelley, Byron, Bentham, Godwin, etc. The

capitalists responded by creating

"mechanics institutes"

with reading material strictly limited to technical subject

matter associated with work. One of the most important men

in struggling for the rights of workers was

W. P. Roberts, a solicitor.

He was a major figure in the Great Strike of 1844 (see Coal

Mining).

Yarn is quite interesting. It could be sold outside Great

Britain to secure profit, but how might yarn be used within

Great Britain? The "other half" of the cloth industry is the

weaving industry. Development of the domestic weaving

industry to support the export of cloth and take over the

great Colonial cloth industries such as in India, France,

China, etc. (to seek external markets) must yet be discussed.

The household spinning wheel had been used for many years.

The spinning wheel was used for cotton, flax, wool, and

silk. The spinning wheel had a spindle that was horizontal

to collect yarn. The way that the spindle was constructed

resulted in yarn collecting in a pyramidal shape or a

elliptical shape. One variant of the spinning wheel was

called the Saxony or Liepzig wheel, used for flax, but

the Saxony wheel used a more advanced kind of spindle with

a "flyer"

that collected yarn evenly and with the same tension on a

"bobbin". In 1769, Richard

Arkwright designed and constructed the first roller-spinner,

powered by a horse, an example of a "trapiche",

commonly used in the New World on slave plantations to

process sugarcane. Cloth "power spinners"

mills usually use a power source limited to either water-mills

or steam-engines. Almost simultaneously (1770), Hargreaves

designed the spinning "jenny".

This was an advance in that eight spinning wheels were

mounted on a single, common, axle, with vertical spindles.

Unfortunately, the jenny often broke yarn. In 1771,

Arkwright in conjunction with Mead and Strutt replaced

the horse trapiche by a water-wheel. Crompton designed

the "spinning-mule" which is

an advance on the jenny as aside from having the equivalent

of sixteen spinning wheels (it has 16 spindles), it doesn't

break yarn as the jenny does, and it is powered by a

water-mill! In 1775, Arkwright builds a mill on the Durwent

with vertical flyer-and-bobbin spindles. In 1775, the first

true yarn mill using power spinners, called the Cromford water

frame was created. In 1779, at Stockport, the

"slubbling billy"

was created. It uses wool, and combines the jenny with

the mule. Finally, in 1785, the steam engine was used as

a power source by Boulton and Watt at Nottinghamshire.

Hand "warping" machines allowed

warp filaments long enough to be collected into a heap and

more easily handled, all the filaments of the same length.

Click to see hand warping machine.

The warped yarn was then used on looms.

Headdles allowed the loom to

weave warp with woof fibers. Different shuttles could be

strung to different materials such as wool, flax, etc., or

yarns of different colors, producing "tweel".

A "batten" was used to push the

woof back towards where the cloth accumulates. The

"headdles" are composed of

hooks to which the warp filaments or yarn is attached. It

was then possible to attach foot-operated

"treadles" that selected a

headdle and raise the headdle, thereby catching or engaging

the warp yarns, and another foot treadle to pull down and

remove the warp yarns from the hooks on the headdle.

Thus the different headdles could then be selected to get

different patterns. Warp and woof could alternate different

fibers: wool, cotton, flax, and silk successively and in

different colors. This is called "draught"

and "cording". Mr. John Kay of

Bury [separate figure] improved the loom by inventing his

shuttle, which is selected by a "picking peg".

It was originally used for woolens in 1738, then cottons

in 1760. (Add Figure 97.) The design of a pattern for

selecting warp yarns by specific headdles was called

"drawing a warp". The plan of

the sequence of headdles was called a

"drought". Connecting the

headdles to treadles in the correct sequence was called

"cording". However, the warp

yarns tended to get tangled, filaments of yarn unraveled and

the warp yarns were not at equal tension. To remove this

problem, a paste, originally of a starchy flour (called a

"dressing" or

"sizing") was brushed on the

warp to smooth the filaments as well as stiffen them. A

comb was used to clear away knots and partially unraveled

yarn filaments. The humidity due to the dressing was removed

by a fanning action.

A water-powered "power-loom" was

invented circa 1785 by Dr. Edmund Cartwright, who then

successfully used steam power in 1792. In 1796 Robert Miller

of Glasgow, with John Montieth in 1801, started a power loom mill.

However, it was necessary to run the looms intermittently to allow

dressing of the warp. Such intermittent action prevented successful

use of such machines. This dressing problem was solved in 1803 and

1804 by Radcliffe and Ross, with the help of Thomas Johnson in

Stockport (Manchester). They solved the problem of dressing the

warp as follows:

The warp passes through a hot dressing of starch and is then

compressed between two rollers to extrude most of the moisture.

The warp is finally drawn over a succession of tin cylinders

heated by steam, which dries the dressed warp, aided by

revolving fanners. The power-loom was born! As a consequence,

the employment of hand-spinners and hand-weavers rapidly

declined, and the need for factory operatives was created.

The three major foundations of the Industrial Revolution

were the cloth (and related) industries; the coal and

iron mines (coal provided fuel for the steam engines and

iron was used to build the steam engines); and the slave

estates in the New World, Africa and India, which

provided capital that could be invested in machines and

mines as well as markets to sell cloth. The British

government engaged in a movement to abolish slavery which

was carefully targeted to the Atlantic slave trade, but by

no means opposed to slavery elsewhere! The purpose of this

Abolitionist movement was

to prevent capital formation in other countries such as

France and the Islamic-based countries trading in Africa,

to prevent these competitor countries from establishing

and elaborating their own Industrial Revolutions. However,

the Abolitionist movement had another very serious objective:

to replace New World slavery by

Colonialism. Why transport

slaves at high expense to the New World, when they could be

exploited exactly where they were located to begin with?

Indeed, "Buxton's government-sponsored expedition up the

Niger of 1841 was premised on the expectation that ... [would]...

"result in 'bringing forward into the world millions of consumers.@" Abolition of the Transatlantic

slave trade was far from independent of the "slavery"

practiced back in Britain. Slaves were bought partly by

barter using cloth in this process of barter, and plantation

slaves were "paid" in cloth as well. Thus the cloth

manufacturers in Manchester did not want slavery to end%.

The issues of Slavery and Colonialism will not be discussed any

further here. However, the theme of Slavery and Colonialism

did appear in novels by Charles Dickens ("Little Dorrit" and

"Bleak House" for example).

(See Footnote #1 on previous page.)

Much of this discussion is based upon "The Condition of the

Working Class in England", by Friedrich Engels.

© Copyright 2006 - 2019

The Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg Trust

Web Site Terms of Use

Web Site Terms of Use